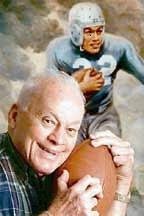

Forever Saturday's Hero

"CHOO CHOO"

"CHOO CHOO"By RICK GUNTER

Journal Editor

CREWE, VA, Oct. 23, 2003 -- A few years ago, Charlie ''Choo Choo" Justice learned that a youngster who was dying in the North Carolina Baptist Hospital in Winston-Salem wanted an autographed photo of the former gridiron legend. The autograph represented the last request of the dying boy.

Mr. Justice autographed the photo for the child. Instead of mailing it to him, he got a friend to drive him to the hospital where he presented it to the young man.

That simple story tells more about the decency and genuineness of "Choo Choo" Justice than anything he ever did on the football fields of the nation.

Maybe such recollections would not be so poignant a few days after Mr. Justice's death had he not been a sports icon. But in a brutal business of users and exploiters that is college and professional football, Charlie Justice was instead a gentleman until the end. His fame did not corrupt him.

His death last Friday, Oct. 17, 2003, at his Cherryville, N.C., home at the age of 79 deeply touches legions of people who remember him or were influenced by him. It is hard to remember a death of anyone outside my immediate family that has touched me so deeply.

My late father, who loved football with a passion and who introduced me to the game, revered "Choo Choo," who became the first football star I remember growing up in the shadows of Mr. Justice's hometown of Asheville, N.C., which one day would be my hometown, too.

I may have some of this wrong, but I recall as a very young child in the late 1940s sitting with my dad in his Ford outside a relative's house in Kingsport, Tenn. Dad had the car radio tuned into that Saturday's North Carolina game. I believe it was against the College of William and Mary.

Anyway, the opponent kicked off to Carolina and Charlie Justice ran down a sideline for a touchdown. A teammate was flagged on the play and the score was erased.

The opponent again kicked to Mr. Justice, who speedily took the ball down the other sideline to score again. This one counted.

In 1974, the University of North Carolina at Asheville had the good idea to name its gym in honor of Mr. Justice. At a luncheon, the university showed a highlight film of the honoree. The most memorable footage came from a game between Carolina and Gen. Robert Neyland's Tennessee Volunteers. Honestly, I think "Choo Choo" ran past every Tennessee defender at least twice on his way to the end zone.

It may have been in that same game that Mr. Justice returned a punt for a touchdown against Tennessee. General Neyland called it the greatest run he ever saw in football.

Charlie Justice was the most dazzling broken field runner I have seen, and I have seen many.

Mr. Justice always said he learned his running style when he and a brother romped through the Christmas season crowds on Asheville's Pack Square.

Until the end of his life, Charlie Justice was what once was called a "good old country boy" who knew right from wrong and gave others the credit for his success.

One of the amazing things about him is that he always credited his teammates with being more worthy of attention than he. He would laud Crewe's Johnny Clements, who shared the backfield with him at Carolina. He was full of praise for Art Weiner, who caught so many passes from Mr. Justice, for Paul Rizzo, one of his blocking backs, end and place-kicker Bob Cox, and rugged center Joe Neikirk (who became vice chairman of the Norfolk Southern).

He would tell the press of the contributions of tackle Ted Hazelwood, a huge lineman in the late 1940s at 238 pounds, and guard Sid Varney.

There were so many others, including guard Ralph Strayhorn, fullback Bobby Koonts, end Ed Bilpuch, backup tailback Bud Carson, wingback Jim Camp, guard Dick Bestwick, and blocking back Don Hartig.

Mr. Justice and his teammates came along at the right time in the history of North Carolina and Southern football. After a protracted and bloody world war, the public needed relief from that long stint.

"Choo Choo" Justice -- a nickname given to him by a Navy teammate before Mr. Justice enrolled at North Carolina -- and his teammates provided that relief. They gave tens of thousands of people something to cheer about.

They gave North Carolina its golden era in football, a period now known as "the Justice Era," a designation "Choo Choo" did not like.

But deep down inside his heart, Charlie Justice had to know that he had God-given ability to perform on a football field. He had the instincts, the dodging and spinning ability that the single-wing of his college coach, Carl "the Gray Fox" Snavely, used to showcase his star pupil's skills.

In a lineup, Charlie Justice would not have been picked out as a football star. He weighed about 165 pounds and was short in stature even for his era of competition. He was a handsome young man, with dark hair, a strong jaw, and an easy smile. But he would not have been sent over by Hollywood's Central Casting to play the part of a football player.

My Asheville friend Dick Kaplan, who wrote about Mr. Justice for years, told the story that when the footballer went out for the star-studded Bainbridge. Md., Naval Training Station team, they could not find a uniform to fit him.

He wandered off to one end of the practice field where he was playing around with a football, unnoticed by coaches. But he happened to kick a ball that sailed for yards. The scene caught the eye of coach Paul Brown, who wanted to know who kicked that ball!

Mr. Brown approached "Choo Choo" and asked him if he could duplicate the kick. He did.

After that, the Navy found a uniform for Charlie Justice!

He entered the Navy after an awesome high school career at the old Lee Edwards High School in Asheville that was to be renamed Asheville High.

In high school, Charlie Justice averaged an incredible 14 yards a carry for three seasons. In his senior year, 1942, he ran the ball 128 times for 2,385 yards, scoring 27 touchdowns and 172 points. He averaged an unbelievable 41.37 yards on his touchdown runs. He helped the Maroon Devils outscore opponents 441-6. That team, incidentally, is still regarded as the greatest in the history of Western North Carolina prep football. Mr. Justice was the last surviving member of the 1942 team.

He already had come a long way for a youngster born in Buncombe County, N.C.'s Emma section and who long would be haunted by heart problems.

He had at least 50 football scholarship offers after his naval service. He wanted to attend the University of South Carolina. That was largely because Mr. Justice liked the Gamecock coach, Rex Enright.

But Mr. Justice's brother, Jack, could not believe Charlie was headed to South Carolina and told him if he joined the Gamecocks, their relationship was finished.

Years later, Coach Enright told Mr. Justice that he made the right decision by attending UNC, because the Tar Heels simply had a greater supporting cast than was on hand in Columbia.

He did not miss a beat at UNC. He could do it all on a football field -- run, pass, kick, block, and play defense. The featured back in Mr. Snavely's single wing, Charlie Justice ran and passed for 4,883 yards, setting a school record for total offense that stood for nearly half a century.

He led the Tar Heels to 32-9-2 mark and to bowl appearances in three of his four years.

Some writers who covered his UNC career believe his biggest day came in Charlottesville against the Virginia Cavaliers on Nov. 30, 1946. The Tar Heels had to win the game to lock up a berth to the Sugar Bowl.

There was another problem: Charlie Justice had a severely injured knee and his playing in the game was questionable.

He did play hurt and romped for 169 yards, the biggest day of his college career. The great Jake Wade, of the Raleigh News and Observer, began his story of the game this way:

"North Carolina's hell-to-leather Tar Heels thought their Choo Choo special was stalled in the yards with engine trouble but today they boarded the wounded rattler and rode right into the famous Sugar Bowl game on New Year's Day. Carl Snavely's Southern Conference champions knew they had a New Orleans holiday if they won this one today."

Virginia had a good team that year, an explosive squad. But the Cavs were no match that autumn afternoon for Choo Choo and fullback Walt Pupa.

Mr. Justice, badly injured, did not start the game and had not practiced all week. But the Cavs were threatening to spank the Tar Heels and Choo Choo entered the fray and made runs of 54, 45, 13 and 31 yards.

He should have won the Heisman Trophy, signifying the best college player in the country, but came in second in 1948 and 1949. The awards were won by Leon Hart of Notre Dame and the incomparable Doak Walker of Southern Methodist. Mr. Justice earned consensus All-American honors both years. He was recipient of the Maxwell Trophy in 1948 as the best college player in the country.

In the 1950 College All-Star game at Chicago's Soldier Field, "Choo Choo" and his fellow seniors faced the world champion Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League. The game was usually a mismatch, with the pros winning most of the time.

Not that 1950 game. Mr. Justice rushed for 133 yards and was named the most valuable player after the college boys upset the Steve Van Buren-led Eagles.

He played four season with the then lowly Washington Redskins and at one point was the 'Skins' third all-time rushing leader. He was named last year as one of the team's 70 greatest players.

After football, he gave himself to so many worthy causes in North Carolina and helped his alma mater in countless ways.

But the contributions that were his greatest may have been in what could be called the "psychic" area in that his life on and off the football field represented a priceless example to so many young and old people. Scandal never tarnished his name.

Those of us who grew up in his post-football career idolized Mr. Justice and, amazingly, we never found him to have feet of clay.

After all these years, there has not been a player at UNC to come close to being his equal, although many were touted as being "the next Charlie Justice." Oh, some of his records have been broken. But the aura and the legend grow the larger with each passing year.

That legend will flourish, and rightly so, all the more now that he is gone.

When I think of him, I'll remember that twinkle in his eye, that easy manner, and wonder how such a seemingly gentle man could have been such a ferocious competitor on the gridiron.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home